By Leah Nelson (research director at the Alabama Appleseed Center for Law and Justice) and Priya Sarathy Jones, national policy and campaigns director at the Fines and Fees Justice Center.

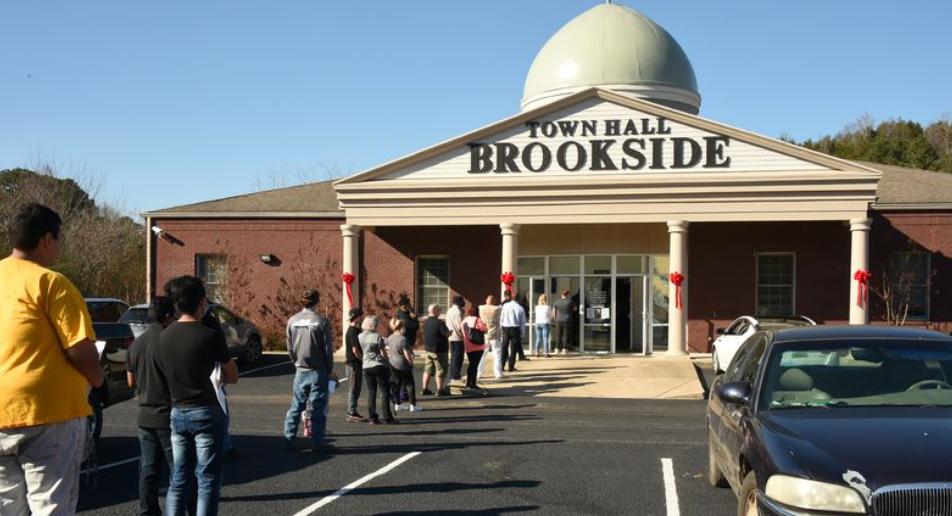

Since news broke last week of how police in Brookside, Ala., were preying on motorists to pay their own salaries, all eyes have been on the tiny hamlet that turned its police force into a money-making enterprise. AL.com’s investigative reporting prompted rapid change in the tiny town: Police Chief Mike Jones resigned Tuesday, and on Wednesday Alabama’s Lieutenant Governor requested a state audit of the Brookside police department.

There is no question that Jones — who turned Brookside into a poster child for policing for profit — needed to go. But treating the symptom doesn’t mean we’ve cured the disease.

In Alabama, like most of the U.S., criminal justice policy and tax policy are two sides of the same coin. Relying on crime to keep revenue flowing is an implicit bet against public safety — if crime goes down, so does revenue. A 2019 Governing report found that fines and forfeitures account for more than 10% of general fund revenues for nearly 600 jurisdictions. The worst offenders were places whose residents could least afford it: jurisdictions where fines accounted for over 20% of general fund revenues had median household incomes less than $40,000.

Turning law enforcement into armed debt collectors erodes the trust between community and law enforcement. It keeps no one safe.

Financial penalties weigh heavily on people who cannot afford to pay immediately. Debtors’ prisons are illegal in the U.S., but a 2018 study by Alabama Appleseed found that nearly 50% of Alabamians who owed criminal justice debt were jailed because they couldn’t keep up with their payments. To avoid jail, many made desperate choices: 83% chose not to pay for basic needs like rent, utilities, or medicine; 44% took out a high-cost payday loan; and 38% turned to crime to get the money they needed to stay out of jail — most often selling drugs, stealing, or sex work.

Putting a stop to policing-for-profit requires policy change. To prevent predatory policing, hold police and courts accountable for their behavior, and mitigate the harm caused by excessive fines and taxes disguised as fees, we must untangle criminal justice policy from fiscal policy.

We can start by eliminating criminal justice fees, which are a wildly regressive tax. While fines are meant to hold people accountable, the sole purpose of fees and court costs is to generate revenue to support basic government operations. The vast majority of U.S. voters believe everyone should pay for the justice system, not just those charged with a crime.

States should also require that all fines and fees be remitted to a state’s general fund. This removes the direct incentive to make unnecessary or questionable stops as a fallback measure to raise revenue, while leaving local governments free to prioritize public safety needs.

At the same time, lawmakers should cap the percentage of a municipal budget that can come from policing for profit. Nearly half of Brookside’s total budget came from fines and forfeitures. While caps do not fully untangle policing from revenue, they erect guardrails to prevent the abuses highlighted in Brookside and jurisdictions like it all around the country.

At a bare minimum, states must develop standards for the operations of municipal police and courts. These should include collecting and publicly reporting data on traffic stops to monitor the demographics of who is being pulled over and why, who is being convicted of what offenses, and how they are being punished.

And critically, states must take immediate steps to mitigate the harms of the current system — by eliminating counterproductive penalties for nonpayment, such as late fees and driver’s license suspensions.

Every day in the U.S., people are assessed fines and fees they cannot afford. These excessive penalties trigger a cascade of collateral consequences that cause irreparable harm, particularly to low-wealth Black and brown people — who are overrepresented in the criminal justice system and less likely than their white peers to have access to wealth.

Brookside is an extreme case, but rooting out the town’s corruption and venality does not get at the root of the problem: using fines and fees as a hidden tax. Only policy change can do that. Lawmakers must take action to rein in the perverse incentives that foster predatory policing. Justice demands it.